This might be because artists’ anti-fascist efforts cannot easily be classified as mainstream art. They are also much harder to capitalise, like any creative act that is not only aesthetic but also openly political in nature. Anti-fascism is also not compatible with what we can find in textbooks and anthologies describing art as a history of the evolution of forms and focusing on innovations, turning points, key dates, and a succession of big names. Many forms, images, motives, and gestures, as well as artistic strategies and tactics conceived and employed by anti-fascist artists, such as protest, occupation, aid collection, demonstration, or street propaganda, continue to be used today, reappearing wherever artistic circles are standing up against fascist policies, discourse, and symbols.

An anti-fascist attitude is also not in harmony with the default understanding of art as an independent, autonomous sphere, detached from the world that surrounds it and centred on its own history and development. Having an anti-fascist attitude means unequivocally embracing art that is directly engaged with the world, one that uses artistic competencies and creative imagination to influence reality: express disagreement, resist, condemn violence, mobilise, demand change, stem some social, political and cultural processes and sustain others, or create viable alternatives to the reality around us.

In this text, we would first like to offer an alternative look at the history of 20th-century Western art: we will look at it through the prism of anti-fascist attitudes and efforts, referring to activities undertaken from the interwar period to the second decade of the 21st century. Second, we will share some tips on how to become an anti-fascist artist today: we will explain what an anti-fascist attitude and efforts are, and we will show how anti-fascist practices at the intersection of art and non-non-art can be used today.

Disclaimer

Before we go any further, we must first make two important disclaimers. First, this text is written from a specific, hands-on perspective of individuals engaged in studying and practising anti-fascist attitudes in art. We are both art historians by profession, and we work in the Polish art world as researchers, curators, and organisers. We are also members of the Office for Post-Artistic Services (Biuro Usług Postartystycznych, BUP)[1]and a Poland-wide network of individuals dabbling in post-artistic practices[2]who cooperate with that Office. In many campaigns and activities that we have co-created or supported, we were inspired by or mentioned past examples of artists’ anti-fascist efforts. Moreover, we have been closely cooperating with Polish anti-fascist circles as part of the BUP for several years now, attempting to support their activities through artistic competencies and creative imagination.

Our interest in the history of anti-fascist art stems from more than just our curiosity as researchers or our desire to be inspired. We began researching this subject (which has eventually led to the creation of this text) as part of the Anti-Fascist Year (Rok Antyfaszystowski) initiative, a “Poland-wide initiative supported by a coalition of public institutions, non-governmental organisations, social movements, collectives, artists and activists”[3]launched in 2019, whose aim is to “oppose the return of neo-fascist movements and those endorsing fascist ideas, discourse, and practices into the public domain”[4]. As part of it, we have co-created the Atlas of the Anti-Fascist Year, i.e. a bottom-up “social archive of anti-fascist and anti-war activities and attitudes in culture, art, and other spheres”[5]. In this text, we describe a range of tactics, strategies, and activities linked to the BUP and Anti-Fascist Year.

Second, we what are sharing is just a fraction of the history of anti-fascist artistic practices. Our research, reflections, and suggestions are grounded in a specific place and time – in Poland, in Eastern Europe, in the second decade of the 21st century, at a time when neo-fascist[6], post-fascist[7] or alt-right[8] discourses, social movements, and political parties are gaining momentum and prominence not only in our country and on our continent but also throughout the world. Because of Poland’s geographical location, and our education and experience, this text discusses the anti-fascist efforts of artists active in the Western world – in Europe and the USA. A similar tale can be woven by looking at fascism and anti-fascism in other places and at other times in history; nevertheless, we leave this task to those who have the theories, concepts, and experience necessary to embark on it.

Fascism? But That Was So Long Ago…

Before we begin to trace anti-fascist efforts through history, we must answer the question of how fascism and anti-fascism are understood in the context of this text. If your intuition tells you that the concept of “fascism” is somewhat unclear or is a handy insult to hurl at whoever you happen to disagree with, then you have a point there. The renowned historian Ian Kershaw once quipped that trying to unequivocally define fascism was like trying to nail jelly to the wall[9]. In our reflections and practices, we embrace the definition proposed by the Italian intellectual Umberto Eco in his famous essayEternal Fascism, in which he describes Italian fascism he experienced as a child and proposes a list of 14 universal characteristics of a fascist mindset and worldview:

- The cult of tradition

- The rejection of modernism

- The cult of action for action’s sake

- Disagreement is treason

- Fear of difference

- Appeal to social frustration

- Obsession with a plot

- The enemy is both strong and weak

- Pacifism is trafficking with the enemy

- Contempt for the weak

- Everybody is educated to become a hero

- The cult of machismo, and militarism

- Selective populism

- Newspeak[10]

Eco emphasises that a mindset, ideas, or political groups can be classified as “fascist” even if they do not display all of the above characteristics. Sometimes even one of these elements is enough to sow the seeds of fascism, and if we are dealing with a mixture of several of them, then we are definitely confronting something “fascist in nature”.

What is anti-fascism, then? Simply put, it is an attitude that is in direct opposition to fascist ideas. As the philosopher Michał Kozłowski puts it, “anti-fascism proposes a certain moral order. Instead of saying that everybody should know their place, it says that there is a place for everybody”.[11]Whereas fascism cultivates tradition and rejects anything contemporary and modern, anti-fascism is open to both the old and the new. Where fascism obsesses about plots and enemies, anti-fascism sees a complicated reality and other people who have the same right to live in their own way. Whereas fascism worships strength and despises weakness, anti-fascism makes sure that the strong support the weak. If fascism demands a uniform, homogeneous society, anti-fascism invites all those who do not accept fascism to a diverse, open coalition.

Although now frequently regarded as a marginal movement, cultivated by the last anarchists, squatters, and local Antifa groups, not so long ago an anti-fascist attitude was taken for granted in the Western world. The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights signed in 1948 is the most important anti-fascist document that is in clear opposition to fascist aspirations[12]. The concept of a world free of fascism formulated by members of an anti-fascist coalition laid the foundations for the development of societies in the 20th century – and on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Structures such as the UN itself or the European Union, established to ensure that fascism would never raise its head again, were built precisely on that concept. Perhaps it is precisely because of the important role that anti-fascism has played in the history of the West that so many artists have been employing art as a tool of anti-fascist resistance and efforts.

Now that we have managed to clarify at least to some extent what fascism and anti-fascism are, we can go on to explain what anti-fascist artistic practices are or may be. In the second part of our text, we will look at different strategies employed by anti-fascist artists and discuss a range of specific examples of such activities.

Open a Museum

The history of artists’ anti-fascist efforts is rooted in the trauma of the First World War. In the face of such terrible cruelty and the immense scale of violence and death, numerous artists devoted themselves to creating works designed to provoke anti-war sentiments: they documented the everyday reality of the war and painted landscapes of wasted battlefields, or veterans’ mangled bodies. Many of these artists engaged in anti-fascist activities in the 1920s and 1930s. With memories of the atrocities of the war still fresh in their minds, they feared that the fascist worship of strength, machismo, and militarism, and the eternal search for enemies would spark another conflict. One of those individuals was Ernst Friedrich, a German anarchist, anti-fascist, and pacifist, renowned for his anti-war book of photographs War against War published in 1924, which “opens with photographs of toy soldiers, cannons, and tanks and ends with photographs of military cemeteries. Between them, Friedrich placed photographs of ruins, slaughter, massacred bodies, war devastation, plundered churches, and burnt houses”[13]. The book features ghastly captions laying bare the consequences of the ideology of war.

A year after the publication of the famous book, Friedrich opened the Anti-War Museum in Berlin, which translated the narrative of the War against War into the medium of exhibition. The institution became a local centre of resistance, bringing together those who opposed not only war but also the increasingly powerful National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP). Meetings and discussions, displays of anti-war and anti-fascist artworks, and campaigns during which people created slogans and banners for demonstrations together were all held at the Museum. After the Nazis rose to power, in 1933 an SA unit destroyed the Museum and arrested Friedrich, who was forced to leave the country. In 1982, his grandson, Tomas Spree, reopened the Anti-War Museum, which continues to enjoy considerable popularity[14].

Call an Assembly

The spectre of fascism returned to haunt all of Europe in the second half of the 1930s. Against this background, artistic circles were becoming increasingly anti-fascist. It was not only openly politically committed artists, such as avowed anarchists, pacifists, or leftists, but also those regarded as more moderate that actively opposed war and violence. In many countries, artists and cultural workers were organising conventions and congresses to discuss art as a tool for fighting what was termed the “fascisation” of cultural and social life, alliances were being formed between artists, political activists, and social movements, experiences and ideas were being exchanged, ties were being forged, and the international anti-fascism movement was growing stronger.

In 1936, committed Polish artists organised the anti-fascist Congress of Cultural Workers for the Defence of Freedom and Progress in Lviv. The aim of the Polish cultural circles was to express their opposition to fascist and authoritarian tendencies in the country’s public and political life[15]. In their speeches, the participants proposed carrying out a wide-ranging education reform, introducing committed art to public institutions, putting an end to the government’s efforts to impose censorship, or establishing transparent rules for financing cultural initiatives. The congress was broken up twice by the police and National Radical Camp (ONR) militia, and the organisers were kept under surveillance, persecuted, and attacked in the press for many months.

Many contemporary activities have also been inspired by pre-war congresses of anti-fascist artists, including conventions organised by the Anti-Fascist Year initiative at the Museum of Modern Art (Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej) in Warsaw in 2018-2020, the Arsenał Municipal Gallery (Galeria Miejska Arsenał) in Poznań, the Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art (Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej “Łaźnia”) in Gdańsk, and the Centre of Polish Sculpture (Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej) in Orońsko, or the international congress of activist and artistic anti-fascist groups and organisations held as part of the documenta 14 exhibitions in Kassel and in Athens in 2017[16].

Set Up a Grassroots Organisation

In the 1930s, artists throughout the world began setting up organisations bringing together individuals who used their creativity to wage a visual and propaganda fight against fascism. The American Artists’ Congress (AAC), bringing together American anti-fascist artists working together under the slogan “Against War and Fascism”, was set up in the USA in 1936[17]. By the end of the Second World War, over 1,000 artists who tried to promote public, accessible and popular anti-fascist art had joined the AAC. They created illustrations and caricatures for magazines, as well as leaflets and posters, and organised annual congresses, exhibitions, and urban plein-air workshops (including in New York’s Times Square) during which artists painting live collected money for anti-fascist organisations in German, Italy, and Spain. Other tactics used by the AAC were boycotts and protests: in 1936 members of the organisation refused to send their works to an exhibition at the Berlin Olympics, in 1937 they refused to take part in the Venice Biennale, and in 1938 they organised a protest at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, demanding that the institution remove Christmas cards produced in Nazi Germany from their offer.

Similar grassroots anti-fascist organisations bringing together anti-fascist artists and cultural workers, such as the already mentioned Anti-Fascist Year, can be found in many parts of the world today. The Die Vielen (“The Many”)[18]association, which organises loud, spectacular protests and demonstrations, brings together anti-fascist-minded cultural sector workers, and promotes democracy, solidarity, and creative freedom, opposing the return of neo-Nazi movements to social and political life in Germany, has been in operation in Berlin since 2017. Still another example is the Greek Anti-Fascist Culture initiative, which has been inspiring cultural and artistic circles to fight against neo-fascist movements and political parties by organising meetings, marches, exhibitions, events, and festivals since 2019, mainly in opposition to the far-right Golden Dawn party (recognised as a criminal organisation by a Greek court in 2020).

Hold an Exhibition

Although a comprehensive publication charting the history of anti-fascist exhibitions has yet to appear, and you could be forgiven for thinking that such undertakings are rare, anti-fascist artists have always employed for their purposes diverse formats taken from the world of art, from grassroots museums, through creative associations and organisations, plein-air workshops and congresses to paintings, graphics, or sculptures and, obviously, exhibitions. Usually, however, they see the role of these formats in a slightly different way than the mainstream art world, regarding them as a tool for anti-fascist propaganda and cultural policy allowing them to publicise, highlight, and publicly expose fascist policies and notions, a way to strengthen and support specific anti-fascist struggles and discourses, or an opportunity to collect money for anti-fascist activities.

Sending Pablo Picasso’s legendary Guernica[19]on an international tour is the best example of such activities. This monumental painting was commissioned for the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. It is a direct response to the brutal bombing of the town of Guernica by the Nazi air force in a show of support for General Franco’s fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War. More than 1,500 people, mostly civilians, were killed in the bombing, which laid waste to a large part of Guernica. The story of the bombing sent shockwaves throughout the world, and Picasso’s work depicting those dramatic events quickly became one of the most famous anti-war and anti-fascist paintings in history. After being exhibited at the World’s Fair, the painting embarked on a global tour: it was exhibited in Stockholm, Oslo, Copenhagen, London, Leeds, Manchester, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago. These exhibitions were important social and political events, drew large crowds and were accompanied by speeches by politicians and activists, demonstrations, public discussions, and collections to raise money and humanitarian aid for anti-fascist forces fighting in Spain.

From around the second decade of the 21st century, anti-fascist exhibitions have been organised in many Western countries in a response to the ever-growing popularity of neo-/post-fascist political parties, social movements, and discourses. In 2019, the Dortmund-based Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV) association organised The Alt-Right Complex – On Right-Wing Populism Online exhibition, which looked at the presence of far-right communities on the internet and social media[20]. TheSteve Bannon: A Propaganda Retrospective exhibition by the Dutch artist Jonas Staalorganised in 2018 in Rotterdam (Het Nieuwe Instituut) centred on the figure of Steve Bannon, a propagandist and Donald Trump’s chief strategist, who contributed to the rise of neo-/post-fascist tendencies in the USA[21]. In Poland, a dozen or so exhibitions were held as part of the Anti-Fascist Year in 2019-2020, including at the Museum of Modern Art, the Zachęta Gallery, and the Labyrinth Gallery (Galeria Labirynt)[22]. For many years, anti-fascist exhibitions have also been organised by the Visual Culture Research Centre in Kiev, which has repeatedly come under attack from the Ukrainian far-right for its commitment[23]. Since the start of the full invasion by russia[24] on Ukraine in February 2022, many artists from Ukraine (and beyond) have been making anti-fascist themes the focus of their exhibitions, looking at the growing fascisation of public life in russia and numerous political, social, cultural and aesthetic similarities to the fascist regimes of the 1930s.

Strike, Demonstrate, and Protest

Artists’ anti-fascist efforts were by no means abandoned after the Second World War: despite the fall of Nazism in Germany and fascism in Italy, the world has not seen the end of fascist dictatorships, political parties, and social movements. Since the second half of the 1940s onwards, anti-fascist artists have been involved in other movements and struggles aligned with their anti-fascist ethos: for anti-colonial, feminist, anti-racist and pro-refugee causes, social and economic equality, and the environment. They have been employing strategies and tactics similar to those conceived in the 1920s and 1903s and have been actively opposing any manifestations of fascist policies and mindsets that regularly appear throughout the world, regardless of the local political and economic systems, and the cultural context[25].

In the 1960s, American artists who opposed the US involvement in the Vietnam War frequently invoked the anti-fascist ethos. Many of them considered that the open militarisation, the strengthening of the role of the army, support for authoritarian dictatorships, aggressive imperial foreign policy, and aversion to progressive and emancipatory movements prevalent in the second half of the 1960s were plunging the United States into fascism as a country and society. The Artists’ Protest Committee (APC), whose members included Judy Chicago, Elaine de Koonig, James Rosenquist, or Frank Stella[26], was established in Los Angeles in 1965. The APC became known for its “silent marches” attended by hundreds of artists protesting against the war and manifestations of the fascisation of public life, including those in front of Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and the seat of the RAND Corporation, a conservative, pro-war think-tank. It also managed to organise a mass protest as part of which hundreds works displayed in museums and galleries in Los Angeles were covered with graphics bearing the slogan “Stop” and the APC’s anti-war manifesto for one day.

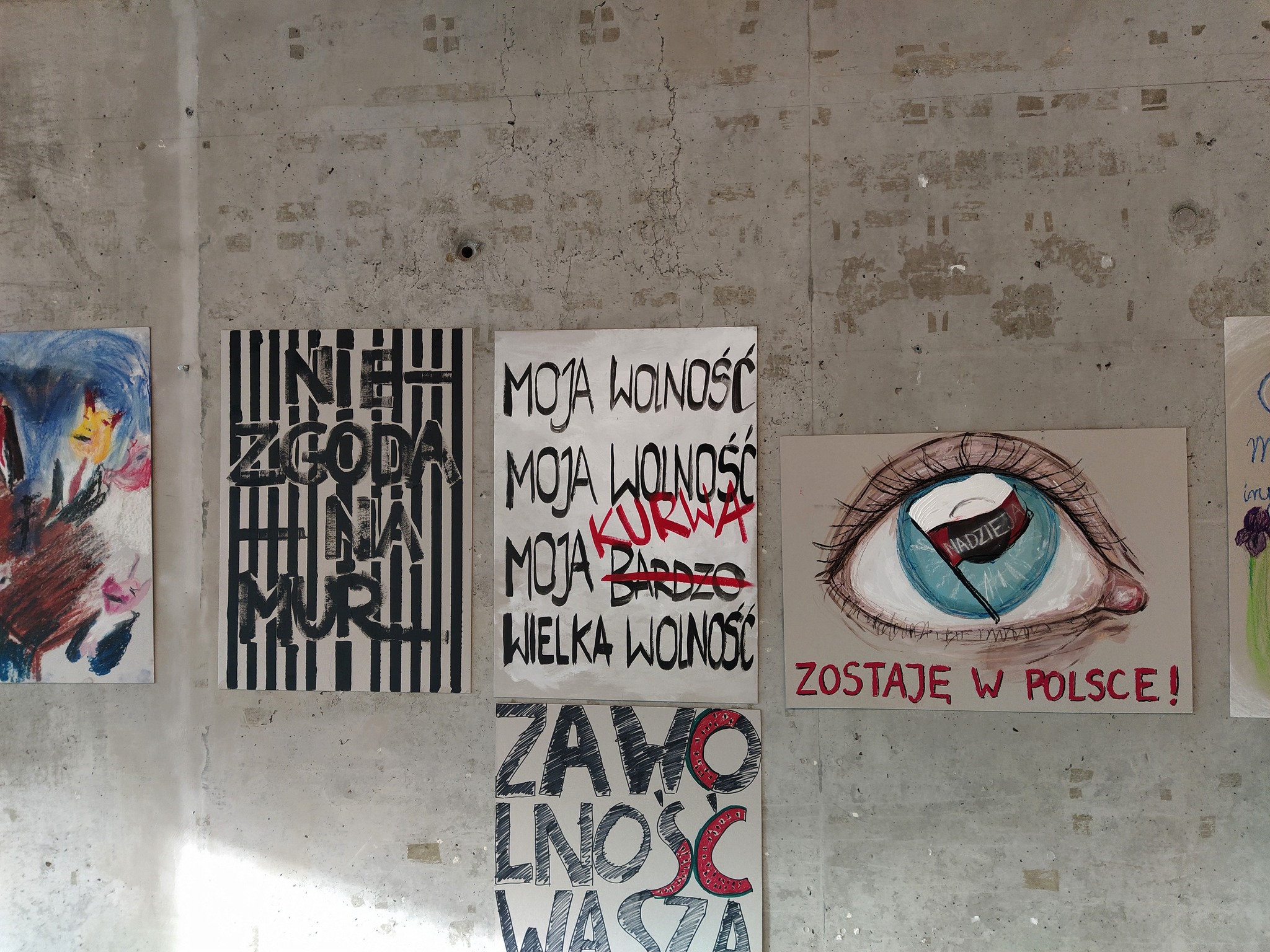

Today, anti-fascist artists continue to rally and participate in numerous protests and demonstrations to oppose the manifestations of what Umberto Eco described as the “eternal fascism”. The #J20 Art Strike campaign, held on 20 January 2017, the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the USA, attracted widespread attention in the United States. On that day, American artistic circles organised a country-wide strike as part of which numerous museums, galleries, concert halls, cinemas, and theatres closed their doors to visitors to protest against “trumpism”, i.e. “a toxic mixture of white supremacy, misogyny, xenophobia, militarism, and oligarchic rule”[27]. During the strike, in some institutions nobody was allowed in, in others there were pickets and demonstrations, and in still others there were open meetings, discussions, and symposiums on global far-right movements. In the second decade of the 21st century, artists in Poland joined protests against changes in the judicial system in 2017 and against the tightening of abortion laws in 2020-2021, anti-racist marches and anti-fascist demonstrations, or numerous protests against russia’s invasion of Ukraine[28].

Engage in Street Propaganda

Street propaganda is one of the most popular forms of anti-fascist art. From the very beginning, painted symbols, murals, posters, leaflets, and sticker art have served as important tools for artists supporting anti-fascist movements. In the popular imagination, anti-fascism is associated with the Three Arrows symbol, designed in 1931 for the Iron Front organisation as part of the “Three Arrows against the Swastika” campaign[29]. The campaign was the brainchild of Sergei Chakhotin and Carlo Mierendorff, who were inspired by pioneering research on the visual dimension of mass culture and the artwork of Russian avant-garde artists. While the symbol they created, nowadays most frequently interpreted as a symbol of opposition to war, fascism, and nationalism, was initially intended to be used to cross out Nazi swastikas on walls, it proved to be so effective and appealing that it is still in use today. Over the nearly 100 years since its conception, it was repeatedly redefined, altered, and re-used in different contexts throughout the world, but always as a symbol of anti-fascist commitment.

The Berlin-based dadaist John Heartfield, one of the most renowned anti-fascist artists in the history of Europe, also employed visual propaganda. Before finding their way to museums and galleries, his famous works, scathing collages lampooning the NSDAP, the fascisation of society, or Adolf Hitler himself, were used as cover art for Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung, the second most popular magazine in Germany at the time[30]. In his works, Heartfield combined avant-garde techniques (collage was still a new technique at the time) with an anti-fascist social and political message. One of the slogans he was guided by was “Use Photography as a Weapon”. His works attracted huge attention: at the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, as the NSDAP was gradually gaining full control of Germany, the covers designed by Heartfield, exposing the hypocrisy and brutality of the fascist policy, could be found at every newsstand on every street corner. Heartfield was persecuted by the Nazis. Although forced to flee from Germany in 1933, he continued his propaganda work.

The American conceptual and feminist artist Martha Rosler engaged in similar activities at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. Her anti-war collages, known today as the House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home series,in which idealised interiors of American suburban houses are juxtaposed with documentary photographs of atrocities committed during the Vietnam War, were originally not conceived as works of art. Rosler created them at home, in response to reports from the war front, and photocopied as leaflets and posters which she handed out at anti-war, anti-racist and anti-fascist demonstrations in the United States and put up on the streets of American cities. It was not until the Vietnam War had ended that she captured the attention of the art world.

Contemporary artists are also involved in creating and distributing ant-fascist visual propaganda. They design posters, leaflets, memes, symbols, and graphics which they distribute on the streets and on the internet and social media, frequently allowing activists and committed individuals to use them freely. The most famous example of such activities in the 21st century in Poland is the lightning symbol designed by the graphic artist Ola Jasionowska for the Women’s Strike, which has become a universal symbol of resistance to patriarchal violence in Poland[31], or the activities of the Archive of Public Protests (Archiwum Protestów Publicznych) collective.[32]

Use Your Imagination!

The history of anti-fascist artistic practices is full of activities harnessing the power of imagination. A good example is the Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art, a collective experimental art workshop whose members included Jackson Pollock, run by the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros since 1936. Members of the Laboratory created public anti-fascist works of art, modern in form and scathingly political in content, in the form of murals, paintings, or fabrics, and designed spectacular scenery elements, banners, and platforms for demonstrations organised by the American League Against War and Fascism[33].

Daring imagination was also the driving force behind the American Artists’ Protest Committee, which rented an unused plot at the heart of Los Angeles in 1965 and erected a giant sculpture-exhibition there, known as the Artists’ Tower of Protest[34], in a gesture of protest against the Vietnam War and the manifestations of fascism in politics, culture and public life in the USA. As many as 400 anti-war and anti-fascist panels created by artists such as Nancy Spero, Roy Liechtenstein, Ad Reinhardt, Eva Hesse, Donald Judd, James Rosenquist, Mark Rothko, Judy Chicago, or Robert Motherwell, were put up on the structure designed by Mark di Suvero. The work received widespread media coverage, and the square around the tower became a place for numerous meetings, demonstrations, and protests for 3 months, serving as a public space for discussing the Vietnam War and its consequences.

There are also many contemporary examples. In 2017, the German Centre for Political Beauty collective overnight put up a copy of a Holocaust memorial near the house of the nationalist politician Björn Höcke in a gesture of protest against his anti-Semitic remarks. In Poland, in the second decade of the 21st century, artists brought classic anti-fascist paintings to demonstrations, thus bringing to life the vision depicted by the painting Demonstration of Paintings by Henryk Streng, recreated Tadeusz Kantor’s happening The Letter in a gesture of resistance to the attempts to organise a “postal election” during the COVID-19 pandemic,[35]or performed choreographed routines with huge flags with modern interpretations of the Three Arrows symbol printed on them as part of an anti-fascist street party organised on 11 November (National Independence Day) in opposition to the Independence March.[36]

Organisations, support networks, alternative institutions, congresses, exhibitions of committed art, street and online propaganda, demonstrations, strikes, and protests: as shown by our brief overview, these kinds of strategies, tactics, and approaches have been developed by anti-fascist artists for a long time and occupy a prominent place both in the world of art and in the world of activism. What all these practices have in common is not only their roots in the anti-fascist ethos and attitudes but also the use of artistic competencies and tools derived from the order of art for the benefit of socially and politically engaged activities. If there is a single most important lesson to be learned from all these examples, it is that unfettered, creative imagination is the best weapon that artists can use against fascism.

[1] https://krolikokaczki.pl/biuro-uslug-postartystycznych/

[2] https://krolikokaczki.pl/krolikokaczki/

[3] www.rokantyfaszystowski.org

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Enzo Traverso, The New Faces of Fascism, transl. Marcin Kowalewski, Znak, Kraków 2020.

[7] Gáspár Miklós Tamás, On Post-Fascism. The Degradation of Universal Citizenship, [in:] Piotr Grzymisławski, Przemysław Wielgosz (ed.), Atlas planetarnej przemocy [The Atlas of Planetary Violence], Biennale Warszawa, Warsaw 201, p. 18-31.

[8] George Hawley, Making Sense of the Alt-Right, Columbia University Press, New York 2017.

[9] Michał Kozłowski, Sebastian Cichocki, Jakub Depczyński, Marianna Dobkowska, Bogna Stefańska, Kuba Szreder (ed.), Jak rozmawiać o antyfaszyzmie przy wspólnym stole? [How to Talk about Anti-Fascism at a Family Dinner?], Warsaw 2023, p. 39.

[10] Based on U. Eco, Eternal Fascism, https://pl.anarchistlibraries.net/library/umberto-eco-wieczny-faszyzm.

[11] Michał Kozłowski, Dlaczego antyfaszyzm? [Why Anti-Fascism?], [in:] Sebastian Cichocki, Jakub Depczyński, Marianna Dobkowska, Michał Kozłowski, Bogna Stefańska, Kuba Szreder (ed.), Jak rozmawiać o antyfaszyzmie przy wspólnym stole? [How to Talk about Anti-Fascism at a Family Dinner?], Warsaw 2023, p. 3.

[12] Ibid, p. 6.

[13] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/wojna-wojnie/

[14] https://anti-kriegs-museum.de/en/start-english/

[15] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/lwowski-zjazd-pracownikow-kultury/

[16] https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-programs/927/the-parliament-of-bodies

[17] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/american-artists-congress/

[19] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/guernica-pablo-picasso/, David Crowley, Guernica: Warszawa, Londyn, Monachium, Nowy Jork [Guernica: Warsaw, London, Munich, New York], [in:] Nigdy więcej. Sztuka przeciw wojnie i faszyzmowi w XX i XXI wieku [Never Again. Art against War and Fascism in the 20th and 21st Centuries].

[20] https://www.hmkv.de/shop-en/shop-detail/the-alt-right-complex-on-right-wing-populism-online-publication.html.

[21] https://www.printedmatter.org/catalog/53025/.

[22] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/wydarzenia/.

[24] The name of this country is spelt in lower case in this text, as proposed by many anti-fascist activists from Ukraine. We see this as a symbol of disagreement with the imperial, neo-fascist policy of modern Russia and a gesture of solidarity with Ukraine, which is fighting an anti-fascist defensive war against the russian invasion at the time when we are writing this text.

[25] Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works, transl. Antoni Gustowski, Aleksandra Stelmach, Warsaw 2021.

[26] Jakub Depczyński, Bogna Stefańska, Aleksy Wójtowicz, Robotnice sztuki przeciw faszyzmowi. Kalendarium antyfaszystowskich i antywojennych działań artystek w XX i XXI wieku [Art Workers against Fascism. A List of Anti-Fascist and Anti-War Activities by Artists in the 20th and 21st Centuries], [in:] Joanna Mytkowska, Katarzyna Szotkowska-Beylin (ed.), Nigdy więcej. Sztuka przeciw wojnie i faszyzmowi w XX i XXI wieku [Never Again. Art against War and Fascism in the 20th and 21st Centuries], Warsaw 2019, p. 181.

[27] Ibid, p. 193.

[28] Examples of such activities can be found in the www.krolikokaczki.pl internet archive

[29] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/trzy-strzaly/

[30] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/john-heartfield/

[31] https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/10053-plakacistka-zaangazowana.html.

[32] https://archiwumprotestow.pl/pl/strona-glowna/

[33] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/laboratory-of-modern-techniques-in-art/

[34] https://rokantyfaszystowski.org/artists-tower-of-protest/

[35] https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/8958-siedmioro-wspanialych.html